Goodspeed's book identified approximately 120 residents of Clay County, Arkansas, by occupation. Just over two-fifths were described as "farmer" or "farmer and stockman." About a third were engaged in small-town commerce as "manufacturer," "merchant," or simply "business man." The rest included local officeholders . . . and professional men.Quite aside from the absence of women, the books also slighted urban life. In Lancaster County, Nebraska, the city of Lincoln grew from 13,000 to 55,000 people during the 1880s, much faster than the countryside.

Although Lincoln dwellers comprised more than two-thirds of the county's population when the Chapman team came to Nebraska, only about a fifth of the biographies treated Lincoln residents. Like urban dwellers elsewhere, most ordinary Lincolnites had not (or not yet) distinguished themselves in business or in agriculture. And mug books did not seek primarily to record urban history; they were records of rural and small-town accomplishment. . . .For this reason the books often began with biographies and portraits of presidents and governors.

No matter how fully genealogy appeared in the biographies, it did not determine destiny. Above all, the subject prospered from his own handiwork. . . . Even as these stories expressed individuals' pride in their achievements, they also combined to tell a national history.

White ethnics like Germans were included, but African-Americans as a rule were on their own. Their mug books were often less local and foregrounded the author more, but the underlying motif was similar. As William J. Simmons put it in 1887, "I wish the book to show to the world -- to our oppressors and even our friends -- that the Negro race is still alive."

Casper is studying the phenomenon, not evaluating evidence. His examination suggests that information likely to be missing in these celebratory sources include failures, difficulties never fully surmounted, conflict, and above all any indication of dependence on outside government aid (such as surveying, military procurement, Indian expulsion, and building harbors, roads, and canals) -- anything that might cast doubt on the story of the self-made man.

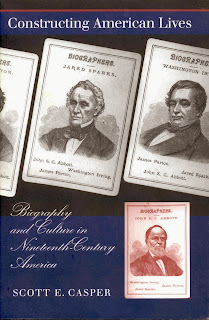

Scott E. Casper, Constructing American Lives: Biography and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999). Snippet-searchable on Google Books.

Harold Henderson, "A cultural historian looks at mug books," Midwestern Microhistory: A Genealogy Blog, posted 30 September 2013 (http://midwesternmicrohistory.blogspot.com : viewed [date]). [Please feel free to link to the specific post if you prefer.]

1 comment:

Often the local-biography coverage was spotty because based on the subjects' having subscribed to the books. In these instances non-subscribers did not have sketches published unless the compiler saw fit to mention them in a general overview part of the volume(s). The sketches submitted by subscribers were often steeped in political views and wishes. It was so much more appealing, for some, to be descended from an unnamed Jamestown or _Ark and Dove_ settler than to originate in Delaware, even if the writer of a brief genealogy could not accurately identify the sketchee's paternal grandfather.

Some of the 19th-century compilers were competent historians and did both consult and incorporate data from local records as well as reminiscences.

As in any published works, the wheat and the chaff may mingle and require evidentiary evaluation on the reader's part.

Post a Comment